British Library, London, Add. MS 34294

Stundenbuch der Sforza

This codex was started for the Duchess of Milan, Bona Sforza around 1486 by an italian illuminator and was completed in the 16th century by a Flemish cooleague. Its colourful and expressive miniatures make it one of the masterpieces of the Renaissance.

A Past Right Out of a Detective Story

Thanks to a coat-of-arms and an inscription in the Book of Hours, it was possible to determine the original proprietor of the manuscript: Bona Sforza, wife of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, duke of Milan from 1466 to 1476.

A first written proof of the existence of this manuscript was found in a letter written by the Milan illuminator Giovan Pietro Birago to an unknown aristocrat in which he tells him that a mendicant had stolen parts of an unfinished manuscript. These stolen leaves, around a third of the entire manuscript, were never found again.

At the beginning of the 16th century, the still incomplete manuscript was inherited by Margaret of Austria who ruled the country on behalf of her minor nephew, the later emperor, Charles V. The remaining pages were not illuminated until around 1520, by no less an artist than the painter Gerard Horenbout.

The remainder of the story is unknown, until the year 1871. However, at this time, an anonymous Spanish grandee sold the work through a mediator to the English conservator Sir John Charles Robinson who passed it on to the English collector John Malcolm of Poltalloch. He divided the manuscript which was then bound in one volume and had it rebound in four individual parts. In 1893 Malcolm donated the manuscript to the British Museum.

Sforza Hours

15th Century

The Italian Part: Giovan Pietro Birago

Birago presumably originates from Milan where he was born around 1450. As early as in the 1470s he started working as an independent painter. In the eighties of the 15th century he painted for leading Venetian families before entering the services of the Sforza in Milan around 1490.

Work on the Book of Hours began probably around 1486/90 but the project was abandoned in 1495 shortly before Bona left Milan. In the above mentioned letter Birago quotes the worth of the manuscript at 500 ducats, which is about five times the value of Leonardo da Vinci’s Virgin of the Rocks. He obviously considered this work as highly important and fascinating because of its artistic value. It is assumed that Birago died around 1513.

The text of the Italian portion was probably written by a single person. The pictures in the margins illustrate either the relevant portion of the book or comment an adjacent line. Birago knew perfectly how to represent the feelings of people through their facial expressions. This expressiveness is further emphasised by the colours he used for his miniatures.

The Flemish Part: Gerard Horenbout

The sixteen Flemish miniatures as well as two ornamental borders are the only works of the illuminator Gerard Horenbout of Ghent which may be proven by documents. Horenbout worked as an illuminator in Ghent since 1487. In 1515 he was appointed painter of the court by Margaret of Austria.

An invoice issued by the master reveals that he had been working on the completion of a Book of Hours before 1521. Later sources remain silent for a few years, until he reappears in 1528 in the environs of the English king for whom he painted until he died in 1544. Horenbout’s illuminations fascinate through their faithfulness to the most minute details, clearly under Italian influence. On the one hand, Horenbout relied on a style of painting widely used in Flanders, on the other hand he certainly tried to model his paintings upon Birago’s style.

A Monumental Work of the Renaissance

The Sforza Hours rank among the masterpieces of the Renaissance, exemplary in terms of colour and expressiveness. Lavish miniatures and golden ornamental borders reveal both atmosphere and emotions prevalent in Renaissance times.

From an art historians point of view, this Book of Hours is a true rarity, as it integrates the major works of two illuminators who worked in different countries and certainly never met each other.

The facsimile edition

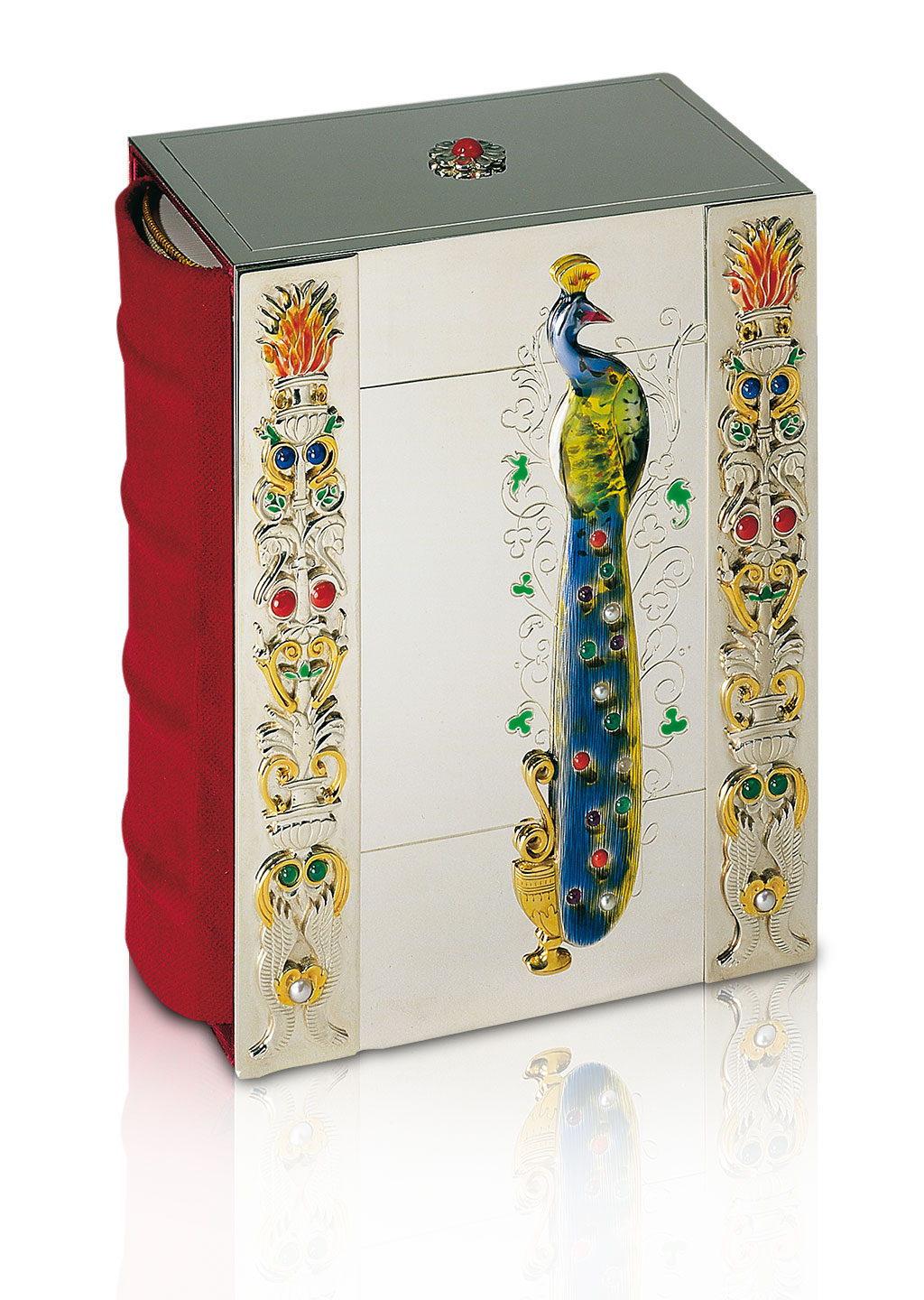

The facsimile is published in four volumes, in full accordance with the original format of 13.1 x 9.3 cm, and in a limited edition of 980 numbered copies. The four volumes are available either individually or as a set. 95 copies were reserved for a de luxe edition of one volume representing the entire work. Out of 696 pages, the integral manuscript contains more than 200 miniature pages and is available in a de luxe sterling silver case set with 30 precious stones.

Volume One contains 80 pages with 44 miniature pages, Volume Two comprises 252 pages including 65 miniatures, Volume Three has 168 pages including 44 miniatures, and Volume Four comprises 50 miniatures on 186 pages. The individual volumes are kept in a protective case covered with red velvet.

The commentary volume

The scientific commentary comprises 860 pages. The following experts have studied the manuscript: Mark Evans, National Museum of Wales, Dr. Bodo Brinkmann, Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt/Main, Dr. Hubert Herkommer, University of Bern.